7. Elevating Food, Women and Responsibility During Wartime

more images below

more images below

Both wars challenged the government to elevate the importance of food production and seemingly mundane daily food habits rooted in the traditionally less important domestic sphere.

“There is no royal road to food conservation. It can be accomplished only though sincere and earnest daily cooperation in the 20,000,000 kitchens and at the 20,000,000 dinner tables of the United States...”

— Herbert Hoover, speaking to the press the day Food Control was signed into law by President Woodrow Wilson, August 10, 1917.“There is no question of the general willingness to do the obvious things, the spectacular things; but plenty of people are going to have to do dull and drab and uninteresting work besides, if we are to win the war. ”

— Elmer Davis, “War Information,” 1943. 28While men performed the “spectacular things,” much of the everyday work on the homefront was left to women. Women were crucial to the success of food conservation campaigns in WWI and later to the success of mandatory rationing during WWII.

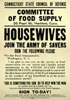

During WWII, millions of women took the Home Front Pledge and agreed to pay no more than the “ceiling prices” set by The Office of Price Administration (OPA), and to use their assigned ration points to help keep wartime inflation in check. They became volunteer price-checkers, reported dishonest pricing and earned new legitimacy and a national purpose for their housewife and consumer statuses.

Women even argued for product grading and price lists they could carry with them while shopping. OPA had empowered them to ask for information and enabled them to become discerning consumers. One administrator referred to OPA as “democracy in action.” The agency's Consumer Advisory Committee reported that housewives “not only accepted rationing as necessary, but have been glad for the assurance it has given them.” 29

Whether rationing was voluntary or not, the conservation of food through canning was a popular subject for posters created during both wars. Canning offered opportunities to depict reassuring images of abundance (instead of sacrifice) and comforting images of women in the role of homemaker and caretaker. Also, businesses appreciated that posters advocating canning did not instruct consumers to buy less of anything.

Where are the Farm Front Posters from World War II?

The collection of WWII posters at the National Agriculture Library (NAL) contains only a handful of USDA or government-sponsored posters designed for farmers in WWII.

Images of farmers were squeezed into messages designed for retail environments or for businesses catering to customers,

if they are seen at all. Purina Mills addressed farmers in one poster

as consumers themselves (in Section 6).

This gap in the collection suggests changes in methods of communication and in the farming profession. In the 1930s, modern technology brought industrialization to farms in addition to problems of overproduction and less work for fewer farmers. Many farmers moved to cities to find work. By the 1940s, rural populations were less isolated from the rest of society thanks to autos, radio and rural delivery. Their numbers were smaller and they were easier for companies like Purina Mills to reach directly. 30

Comparing Posters

Comparing posters from the two time periods highlights the differences in style, use of text and tone. The serious faces and somber references to war and famine in the canning posters from WWI, for example, transform in the later posters into ad-like messages and images full of smiles and free of worry. 31

What did Not Change?

Women remained central in all of the homefront's food-themed posters. Their pivotal role in homefront compliance with war efforts helped to elevate their status as women, but it also cemented gender roles. These posters uniformly depicted women in traditional domestic settings even though WWII marked women's entrance into a typically all-male workforce in unprecedented numbers. 32

Some women questioned the logic of adhering to traditional gender roles in wartime. The 1943 book, Out of the Kitchen — Into War, argued, “The actual Key to Victory in this war is the extrication of women — all women — from the relative unproductively of the kitchen, and the enrolling of them in the high productivity of factory, office and field.”

“Lurking behind the nutrition posters, the committees and conferences, is the hoary notion that in the solemn business of winning a war women's chief contribution should come through more hours of shopping and more conversation about food, meat cuts, vegetables and vitamins... Women's time is expendable — that was the only conclusion you [could] come to.”

— Susan B. Anthony, II, Out of the Kitchen — Into War: Women's Winning Role in the Nation's Drama. 33

Messages about Food

Wartime posters and other media document attempts to persuade homefront audiences to change their behavior, especially food-related behavior. A broad view of these posters, including a comparison of WWI posters with WWII posters, reveals changes in the methods used to persuade, and in the advertising industry trusted by the U.S. government to deliver those messages.

Advertisers not only influenced government methods of communication, but by WWII, they were the government's communicators. Posters sold war, asked for cooperation and informed the public. But they also sold other ideas about American society, especially ideas important to the sellers.

Advertising's messages do not directly reflect reality, but often suggests an idealized version of reality intended to elicit desire — a potentially conflicting goal for a wartime poster. NAL's poster collection provides an opportunity to consider the source and ambitions of public messages in popular media. What messages about food do we hear today? What messages do we not hear? What do they sound and look like? Where do you see them? Who creates them?

Image Gallery |

Section 1 | Exhibit Overview